From river’s wave

I rise my head; and I am all aglow

with light.

Anacreon

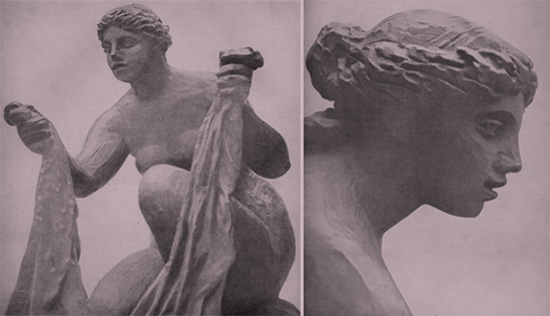

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La grande laveuse accroupie, 1917

The recent book by Paul Haesaerts Renoir sculpteur, published in Belgium by Hermes, documents and illustrates all the sculptural activity of Renoir: 24 pieces including busts, medallions, reliefs, maquettes, large and small statues.

An occasional activity, over a span of 12 years, from 1907, the year in which Renoir made his first sculpture, a medallion of his son Claude to adorn the fireplace of the villa at Cagnes, to 1918, the year of the Danseuse au tamborin and the Joueur de fluteau, two small high reliefs in terracotta.

Twelve years of work, then, not very many, with most pieces carried out by others (only the medallion of 1907 mentioned above, and a bust of the same son in 1908, were made directly by Renoir), because when Vollard convinced Renoir to make sculpture his chronic rheumatism had already stiffened and cramped his hands so badly that his fingernails pierced into the palms. But Vollard, having set aside an initial idea of putting Maillol to work, because in those years the latter already had a well-defined personality, found Richard Guino, a young Catalonian, 23 years old, a student of Maillol, who was able to make the most beautiful and important sculptures. Renoir supervised only the material making, done based on drawings and figures from paintings, limiting himself to indications with a stick tied to his crippled hands as to where something needed to be removed or added, simplified or enlarged. This might raise doubts regarding the authenticity of these sculptures, but the proof that they are by Renoir and his alone is provided by the fact that the personal work of Guino has a cold style, a merely decorative spirit and reflects no influence, no contact with that of the venerable painter.

Others worked for Renoir, after Guino left the studio at Cagnes, but none of them ever had such a sensitive, attentive spirit of interpretation as did this young man. The making of the most beautiful sculptures, from the small Venus to the large one, is owed to his enthusiastic and skillful work as an artisan.

It should be emphasized at this point that the passage from one artistic practice to another, from one medium of expression to another, from painting to sculpture, was a logical one for Renoir, a need he was destined to fulfill due to the great extremes of plasticity and intensity of form he had achieved with the great nudes in his painting.

So for him sculpture is not a new medium of research, in which his personality can increasingly refine itself, but a logical and unavoidable conclusion of his entire life, a sort of apotheosis, we might say – were we not afraid of certain words – of his work itself. An artistic maturity that takes concrete form in volumes, balances, syntheses and definitive, grand rhythms, because at this point they are the only possible means with which to express the rediscovered and renewed virginity of creation, and to reformulate and confirm the rebirth of Myth, the myth of the woman identified with Nature herself, understood as creative force. Now look at the statue shown here; it matters not if it represents a bather or a washerwoman. She is Water, as Renoir correctly called her. This woman on the shore becomes the water itself, the symbol of one of the elements of the world. And Renoir wanted to make, in the same size, a large forgeron to be entitled Le Feu, of which only a small model remains, dated 1916. A blacksmith, the twin of the washerwoman, which would become the image and symbol of fire.

Now you will understand that it no longer matters to know that La grande laveuse accroupie was made in a shack at Cagnes, in the garden of a villa, nor does it matter if we know the epoch of its making and the name of its maker. All that matters is to understand and to sense that this sculpture could only have been conceived on the shores of the Mediterranean. It is so full of light, so harmonious in its composition, so grand and so authentically classical in its spirit and form, that it could not have come to be on any other shores but those faced and reached in the past by the Greeks.

The gesture, this closing in an arch that opens a space, these big lines of the back that converge and rise towards the marine head, the sweeping, solemn gesture of the raised arms and the cloth that descends in a curve, remind us of one of those large seashells that contain and repeat the echo of the sea.

The light that bathes her seems to become moisture, and having just emerged from the water she lingers on the shore, glorious and splendid, engaged in a normal, humble task that becomes solemn here: she seems to turn her head, arms raised, like a reminder of the sea from which she has just come forth.