Giacometti in his studio in Paris

Writing about Alberto Giacometti has always seemed impossible to me: like trying to immobilize, with finite, relative words and concepts, objects that are still in a state of becoming, never finished. It feels like a betrayal of the very principle through which the latest sculpture of Giacometti has been born, or at least a way of perverting the terms with which it appears before our eyes.

Writing about his sculpture, I think I have to run the risk, after having written, of no longer being able to recognize it. Because in discourse and through discourse everything is falsified, or at least reduced to something that is to sculpture what the paraphrasing of poetry is to poetry: senseless prose, because it has been deprived of that mysterious and ineffable essence that made it poetry. Allusion, analogy, suggestion are perhaps the most suitable means. Even better, we can rely on memory and allow his strange “creatures” that at times we are unsure about calling “sculptures” because they are so alive, so true, so atremble, to return in our mind’s eye, like shadows.

We have seen and will see so many things, but I have never seen anything quite so unique as the sculptures of Giacometti, these days. To which realm do they belong, where have they come from, where are they going? They seem to belong to some unknown species, creatures of extreme fragility, materialized in bronze to not escape us and to be able to appear before us, very much alive and distinct, able to be touched, while at the same time seeming like evanescent semblances of surreal dreams; or, more precisely, not belonging to any literary genre, they are none of all this: that are only that which Giacometti truly “sees” and what he attempts to convey with his own means.

Many things are forgotten and no longer appear in the mirror of memory, but certain things linger, and memory returns to them often, as if summoned.

I cannot forget, for example, the deserted studio of Maloja, where the light pours down from big skylights, and in the deserted room lined with pale wood, the air rarified as if in a void, immobile in its white plaster stillness, there is a statue left unfinished. I know not how many years it has been there, perhaps since 1935 or more, tall, nude, slender in its elementary pose, long arms extended at the sides, like an ancient divinity in a forgotten temple. Depending on the angle of the sunlight, its shadow – the only mobile thing in so much stillness – shifts along the pale walls and over the wooden floor until it coincides, at times, with its own drawing, a study as large as the statue, traced with a brush on the wall that is the backdrop.

I saw it for a short time on a transparent September afternoon; I can see it again, as if it were here, as I write, so ‘present’ for me that if I imagine it up there, now that it is deep winter and the snow of Maloja rises to the rooftop, and through the glass screened by its thickness an even more rarified light enters, it makes me shiver, and I would like to cover it up at least for a moment, because it seems to stare at me with icy eyes. It does not stand on a conventional trestle, but as in a child’s pastime it has four small wooden wheels attached at the base, as if it were ready to depart, just as it still is, drawn on a very long, very remote journey. It is an image, an image that by now is indestructible in memory, but I know that it is a statue, a true statue, unfinished and forgotten, that exists up there where it now seems to be just a strange sundial destined to mark a time that does not pass for it.

Alberto Giacometti, The piazza, bronze, 1958

I have never taken indiscreet looks at other people’s correspondence; but the “my dearest children” I inevitably read, to look at a small golden sculpture placed on a desk, at the start of a long letter written in clear script by a gentlewoman of 84, gave me an ineffable sense in that place of love, time and distance. The letter was headed from Maloja to Paris and its writing, the lady told me, represented the only possible way for her to be close to her faraway sons Alberto and Diego, and to spend that long Sunday afternoon with them.

In the peaceful cemetery that surrounds the small church of St. George on two sides – between Stampa and Borgonovo in Val Bregaglia – I saw a river stone placed on a tomb. It seems like a menhir, that stone, or a small dolmen of Brittany, and instead it is a white granite rock the Maira River rolled and polished for centuries, which the loving and respectful hand of a man has completed, adorning it with a dove that quenches its thirst from a bowl. The dove and bowl are a very light relief, crafted with the sensitivity of an Egyptian stele, where the light casts no shadow but the volumes are read more with the caress of a hand than with the eyes. A very beautiful tomb, of extreme simplicity, utterly in tune with the simple grandeur of the place. It is the first sculpture by Giacometti I was able to see in his hometown, an act of love and devotion of an artist son for an artist father.

I know not how or why, but the simplicity of that work spoke to my heart like the opening words of the letter I had happened to read. The same sense of devotion, of love, of things that do not change over the course of time. Nor can I say why I have remembered these things; perhaps to seek a measure, a human sense of the man whose work I set out to discuss, perhaps to know him first as a man and then as an artist, and to trace back to his origins, if only to know where he was born, who were his parents, from whence he came. But recalling the father, the mother, the hometown also seems like a way of getting to know Alberto Giacometti and his background as an artist better.

Those who publish reproductions of Etruscan sculptures in books beside the pulsating figures of Giacometti, saying that his pieces are simply a direct cultural consequence of those works from the past, demonstrate – in my view – that they have understood neither the old nor the new. The Etruscan sculptures – those elongated figures the good mothers of Cerveteri or Tarquinia, on the advice of soothsayers, placed beside the cradles of newborn babies as a propitiatory sign – are and remain sculptures in the round. Their unusual lengthening therefore has its roots in extra-artistic reasons. On those long stems that can be considered their bodies, intrepid little heads blossom with utterly normal proportions, in all their measurements: height, length and depth.

In those of Giacometti, on the other hand, which seem tall only because they are slender, the heads are “also” made like the bodies and belong to those bodies, and only those bodies, in an identity of style and vision that are perfectly logical and unified. The difference – and this signals the demise of the cultural reference that is often detrimentally applied to grant appeal to the rendering – lies entirely in the above-mentioned fact that the sculptures of Giacometti are not sculptures “in the round.” They are, so to speak, “perspective” sculptures, in which one dimension – depth – simultaneously “comes up short” as a real measure with respect to the others, and is in “excess” as a visual sensation.

Alberto Giacometti, Seven Figures and a Head (The Forest), painted plaster, 1950

If any relationship of affinity can exist between what Giacometti does today and what has been done in the past, to identify it we have to go far back in time to look at certain Egyptian sculptures: the figures of Echnaton, and the little queen Karomama, for example. An affinity that finds its point of contact not in a purely formal and stylistic order, or in a cultural reference, but on a much deeper and higher plane, that of the sentiment of man in the world, of his noble dignity, his unbridgeable solitude.

Giacometti’s sculpture is not immobile, it moves, it is agitated, it continuously breaks at each step on a tormented surface, full of grooves, wounds, clefts, rapidly set clots, and the light finds no peace except along the profiles that unwind the oblong silhouettes. The reason why these figures are lengthened is mysterious, as they almost seek a relationship with the surrounding environment in themselves. Giacometti has repeatedly told me that they always start out normal in their proportions and relationships, but they during the path they take in his hands to become amorphous, living and expressive things they are mutilated, losing volume and body in the attempt to conquer a place in space (almost digging it for themselves) and to identify with what the artist sees, as if they wanted to occupy space only in a vertical direction, in pursuit of a mysterious relationship of scale, of proportion, between real man and a representation the artist is induced to attempt without failing to respect those man-space relationships that exist in reality.

It is in this sense that we can also explain the reason behind the small and minimum sizes of Giacometti’s sculptures, especially some time ago. To live, the statue always requires repose around it, an empty zone; only in this way is it possible to best resolve those small sizes; for the others too much space would be needed: no longer a room, but a certain portion of unencumbered air determined by the sculptures themselves. Obvious the center of Giacometti’s research is not only the question of space – which would then be simply a problem – but as for all real artists it is mainly in the attempt to recreate an object that conveys a sensation as close as possible to the emotion felt “for the first time” by the artist himself at the sight of the subject. All the other things, the more or less theoretical problems, are simply means to achieve this goal; just like clay, plaster and water to be shaped.

The investigation Giacometti has conducted for years and years, continuously drawing from life, has led to such a deep and acute analysis (all his drawing is analytical) that his field of observation is constantly narrowed, to the point of being reduced to a few themes, always the same ones, and furthermore all of an apparent simplicity.

A standing figure, immobile, a seated figure, a figure walking, a head, a bust. It might seem like a very limited field of investigation, a thematic poverty; but what is symptomatic and counts is the way in which these themes are resolved, dug down to the bone, made essential, absolute, irreplaceable, and in which everything is so subtly calculated and resolved that nothing can be changed or moved without upsetting the entire order of the work.

So merciless was the quest that led him in his youth to investigate, to read in the face of man, that at a certain point in his long career as a tireless worker a head became for him a completely unknown object, a thing for which it was hard to find a meaning in the measurements, volumes and form. For years and years, and always twice a year, he stubbornly began two heads, always the same, without ever managing to finish them, with the sole result of putting them aside as merely studies, never as completed works. Finally, getting away from working with a model, with a far from negligible effort of will, he began to work from memory. But to his great surprise and terror he realized that in this attempt of his to remake from memory what he had seen in reality, the sculptures, in his hands and before his eyes, became inexorably smaller and smaller. Then, desperate, he began everything again, from the start, again, but in a few months he found himself at the same point, for the same reasons. A figure, a head, if it was life-size, did not seem true to him, but simply a conventional thing; and if it was small, precisely for its extreme smallness, he found it unbearable: so he continued, for months and years, until with a single blow of the chisel those small creatures ended up in dust. Then for a while he calmed down, accepting that strange and unusual size, only because heads and figures seemed more “true” to him only when they were small. But another surprise was still in store, and it came at the moment in which, in the attempt to make larger figures, he realized that for him they reached a resemblance to the real only when by dint of removing, removing and putting and then inevitably removing again, they became long and slender. So he could only “do it like that” if he did not want to betray himself and his way of seeing. What he does now is simply the result of his profound honesty, of his extreme, even risky way of keeping faith with himself.

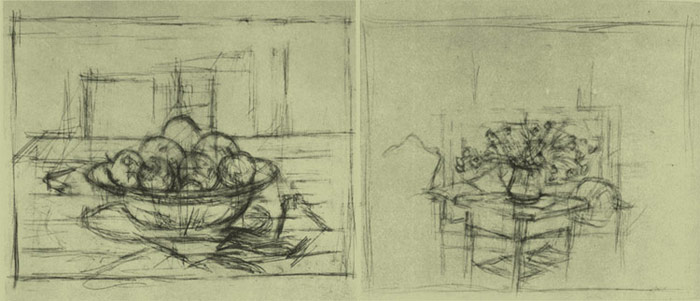

Alberto Giacometti, Fruit Bowl with Apples; Flowerpot on the table. Drawings, 1954

Giacometti can draw everything, everything he sees, everything that comes within range of his vigilant, penetrating gaze; he doesn’t have to arrange poses or choose objects: just one object, one series of objects placed randomly, selected only on the basis of impulse, the need to draw in that moment, and on a sheet of paper a hundred quick, precise signs are ignited, a hundred lines chase each other and intertwine, all seeking the same thing. Talking about Giacometti’s drawing is like talking about his sculpture, because – and it might seem incredible – the “means” he utilizes are identical, the results interchangeable. Giacometti is a tireless draftsman, with a very sharp, aristocratic and refined sensibility. He draws – for example – trees or mountains so economically and at the same time so analytically that equivalents can only be found in the graphic work of Cézanne: such a personal, typical, unmistakable way of drawing.

Drawing – to be clear – of high quality, luminous, serendipitous, excavated on the paper almost in search of what exists behind the objects to give them volume, to place them at the correct, expressive distance. It is his clear, precise, terse, almost cold sign, without trembling and slips, in which pentimenti or corrections are displayed, on the surface, revealed but expressive in their own right, like the others, the correct signs, like the initial, immediate signs “on target.”

His drawings seem to begin from a preordained point, selected so carefully as to seem random, and they are laid out so well, so aptly arrayed on the white of the paper, that the white seems to have been instinctively left there as a binding element, to the proper extent, in the liveliest and most expressive relationship. He often concentrates on a particular that will represent the “focus,” the fulcrum of the page, and from there, from that minute detail, analyzed, dissected to the point of the implausible, everything begins and harmoniously constructs itself in a form that seems to have been already entirely seen and envisioned, so as to proceed quickly, seamlessly, concisely, in a clean, essential composition across the surface. I have seen insignificant, inexpressive and random objects become stupendous architectures of rhythms, lines and forms under Giacometti’s sharp pencil; I have seen the most common and normal things transformed into precious clarity in his vigorous, sensitive hands. Truly, to have a large folder of drawings by Giacometti on your lap, and to slowly leaf through it in the precious silence of the home where he was born, is an unforgettable adventure I would love to be able to experience again and again.

In Giacometti’s works the relationships of volume, form and proportion that develop between the sculptures and the bases from which they arise – they are never simply rested, but bonded by the same material – are visibly pondered and subtly resolved.

And how, in his lucid intelligence, could the artist overlook that bridge on which his sculptures pass in order to occupy space? Only in Brancusi have I seen such attention and calibration – solving a difficult problem of a plastic-architectural order – of the bases, the supports on which the sculptures are placed. For Giacometti they are a living, integral part of the work, the gauge by which those relationships that are subsequently mysteriously established between the sculpture and the space around it are measured, in a stable way, for the first time.

Inexplicably enough, I have always imagined assigning a sound, a voice, to these phantom-like yet real apparitions, born in a world made of emptiness, space, transparency, springing from the earth as from the depths of time.

Like a single cry, a monotone, that echoes in a vast space, filling it: the short, terse noise of two pieces of wood struck together in the immense salle des Pas-perdus of the Palais de Justice of Paris, or in the even larger and even more resonant hall of Palazzo della Ragione in Padua, in which a cry, behind a door that suddenly closes, moves itself like rumbling surf, immediately absorbed, absorbed on high by the stupendous hollows in which it dies, vanishing as if behind an acoustic horizon. Or the cry of the crow in the great silence of the mountains, when even a single sudden sound can suffice to break the tense balance of the snow, detaching the avalanche that with its muted thunder is simply the echo and the effect of that first, sharp cry that immediately becomes abnormal, thrown into the empty basin of silence. Thus would be the voice, were the creatures cast in bronze by Giacometti to have one. This is not stated for some facile game, but to establish in the field of sounds an imaginary relationship not unlike what happens in the field of proportions between Giacometti’s sculptures and the space they influence, and which they require to live. A space that cannot be overlooked, because they always demand it, gathering it around themselves mysteriously, with an emanation that could be said to be magnetic. Proof of this lies in the fact that it could be possible to sense the presence of a sculpture by Giacometti in a space, even were it not visible at first glance.

What more is there in the painting of Giacometti, with respect to the sculpture or the drawing? What is there that is dissimilar, not attuned, that cannot be shifted or exchanged from one field to another of his various efforts? Consistency with oneself, homogeneity, a unitary style, are rarely found today. Matisse, Braque, Picasso can pass with impunity, without losing anything, from painting to sculpture, remaining themselves, in all the uncontaminated clarity of their language. And so in Giacometti these modes of expression, which are only apparently dissimilar, remain one thing only, well rooted in his unmistakable personality. Only the means change, not the modes. His lucid and penetrating gaze remains intact, as does the rapid, essential sign. The problems remain the same, in all their urgency and their arduous solution; the light and the transparency, the sense of man, of his fatal solitude, remain the same. The only added factor is represented by the subtle, precious grays, of great variety, of the quick dark strokes, and certain deep earth tones, certain very vivid aluminizing effects.

Alberto Giacometti, Walking Man, bronze, 1953

To the question as to whether it is «still possible to make sculpture a plausible reality» (a question that for thirty years was a troublesome torment that always drove him, dissatisfied, towards multiple and often tentative experiences), Giacometti has certainly responded in a way that leaves no room for doubt, with extreme clarity, though his innate modesty, his capacity for self-critique, his constant searching still cause him to have doubts today.

«Pendant vingt ans, j’ai eu l’impression que la semaine suivante je serais capable de faire ce que je voulais faire,» he says, and one has the impression that deep inside he is still awaiting that “semaine,” because the fascination of his life lies more in seeking than in discovery: the desperate and constant act of searching satisfies him far more than the pride that might come from the hypothetical certainty of having completed a work, of having discovered a truth.