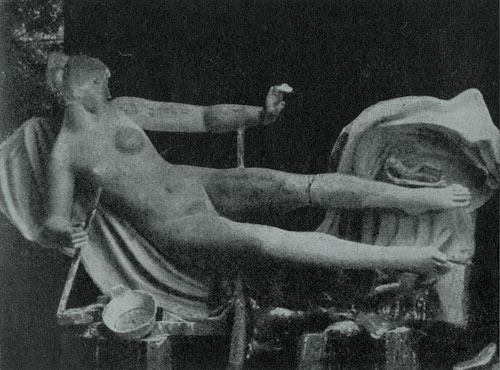

Aristide Maillol, The air, 1939

Reading through the diligent bibliographical note prepared by Giovanni Scheiwiller for the book on Maillol he has published¹, we can regretfully observe that the Italians have been nearly unaware of the work of this great modern sculptor, known and considered outstanding all over the world. In fact, in this long note the Italian names are few and far between, just nine over a span of 20 years, from 1928 to 1948, and not one corresponds to a book, not even a modest one, since they are all connected with articles that have appeared in newspapers and magazines, often with foreign signatures. Having observed this, we cannot help being grateful to Giovanni Scheiwiller who has now added to his well-known series of publications this small but complete, exhaustive and carefully prepared monograph on Aristide Maillol. The critical essay is by Boris Ternovetz, conservator of the Museum of New Western Art of Moscow, with an excellent translation by Giacomo Prampolini. Ternovetz wrote the piece in 1934, and today, sixteen years later, we can still consider it valid, because the work of Maillol continues to be valid and lasting. Since that by now faraway year many things have changed and are still changing in art, but it is comforting to see how the authentic works survive, and that always, in any moment, a discussion about them can be initiated and carried forward with positive conclusions. It is only in this way that the works demonstrate that they belong to time and history.

It is not possible here to outline, step by step, the entire long essay by the Russian critic, but it will suffice to underline the objectivity, expertise and love of deeper study to assure readers of its importance and its value.

After having examined the conditions of French sculpture towards the end of the last century and at the start of ours, dominated by the genius of Rodin, Ternovetz demonstrates how the rise of Maillol’s work truly constitutes the first, authentic and most complete antithesis of the art of Rodin. Then the author tells the story of Maillol and his work: we learn about his education, his activity as a ceramist and creator of rugs and gobelins, and his definitive shift to art as a sculptor, draftsman and illustrator of books. Gauguin looms over Maillol’s youth and determines his artistic evolution: primitivism, the love of simplification, the taste for ornament are decisive factors in Maillol’s background. The passage to sculpture, in which he is self-taught, happens around the age of 40 and was perhaps caused by his great love of and interest in matter, a matter that – unlike yarns and dyes that require a loom, a press, printing plates – can be directly and entirely entrusted to the hands of the artist. As a sculptor he showed work for the first time in 1903, receiving flattering and objective acknowledgment on Rodin’s part; from that year onward, Ternovetz traces back through the work and documents its evolution, which always took place far from any conflict and adventure, in an always linear way, significant in its measured thoughtfulness.

The first work by Maillol contains all the premises for the last, and this fact, nowadays, is so rare and so highly estimable that it would suffice, alone, to document the authenticity and originality of the great Catalan sculptor. He might be said to be detached from time – as he indeed was – operating without haste, lost and immersed in the dream of rediscovering and reviving an ancient classicism as a modern and simple man who possesses, as particular characteristics, the reserve, the austerity, the long development of the idea, the slow perfecting of the substance, the patience and love of a true artisan, with whom he liked to compare himself when he said that he felt his effort was similar to that of a potter. The “classicism” of Maillol and his reference to Greek art, however, seems to be the point that is not sufficiently investigated by Ternovetz. While not exhaustive, nevertheless, the author is very clear and explicit on this score. He speaks of an “imagined and happy antiquity.” Instead, we would say it was rediscovered and recreated, as if it had reached us, through the work of the sculptor, along underground currents brought back to light after centuries, not by chance on the shores of the Mediterranean. And Maillol reminds us of the Greeks only because, like them, in Nature he sees harmony and symmetry, and like them he possesses the equilibrium of volumes, fullness of forms, musical rhythm of movements. This is important because regarding Maillol there has often been talk of “cold classicism” and “academicism.”

This charge is unjust and superficial: the academics, the classicists, are frigid cultural remakers, while Maillol is an artist full of original, luminous and inner vitality, overflowing with a healthy sensuality, chaste and pure, of a natural order, that brings surfaces alive. Only regarding one statement do we find ourselves in total disagreement with the Russian writer, when he sees an escape “into antiquity” in the work of the French sculptor, as a way “both for him and for the class he represents” to escape from the needs of reality and to “barricade himself against contemporary problems.” Certainly Maillol is not Costantin Meunier, nor Vincenzo Vela. We believe that in art – putting aside contingent factors – one must consider and evaluate only the results, the conclusions an artist is able to reach by means of his works, and if he does or does not achieve art. When it comes to critical or artistic evaluation, only this is important, and nothing else. Aristide Maillol was a great artist, of singular force.

Where his relations with the society of his time are concerned, we think this humble old man with a Greek name generously did his part with his work, and if his eyes and soul were not directed towards current events it was because, as a true artist, he had turned them towards an ideal world of a superior order and balance, whose study and contemplation can still, even today, grant benefits to us, the offspring of a time that seems to have lost precisely the sense of any balance. In Catalan dialect, Maillol means a “small vine,” and when we learned this we were happy, as for a discovery, because we have always thought about the slow, careful effort of this sculptor, with which he produced his fruitful results, as a force of Nature, because it resembles nature in its full, fertile rhythm.

Only in this way do the genuine artists insert themselves, making themselves useful and indispensable, in our lives as human beings.

* M. Negri, Aristide Maillol [1950], in Id., All’ombra della scultura, Scheiwiller, Milano 1985, pp. 18-22.