Alberto Giacometti led an uneventful life without any travels or adventures of significance, a life of little interest to biographers, so much so that one might say that Giacometti lived events and adventures only in his work. This is also clear from the letter he wrote to Pierre Matisse in 1948, an animated autobiographical account, a kind of illustrated journal of his activity as a sculptor.

Stampa, a hamlet of few houses and inhabitants on the banks of the Moira stream, is in Val Bregaglia, the long narrow Italian-speaking valley which ascends from Chiavenna to Upper Engadine through the Maloja pass. It is therefore a village of transit under the lee of the mountains, where life is still closely linked to traditions and everyday activities. But the cultural climate of the Giacometti family was in no way narrow or provincial, as one might have supposed from its geographical position. From the heights of Maloja, the valley and beyond was overshadowed by the great presence of the painter Segantini, of whom Giacometti’s father, Giovanni, was for a time assistant and then friend. It may well be that the powerful personality of the painter from Arco influenced and conditioned the cultural life of the area.

Giovanni Giacometti was a receptive and highly cultured person who had studied and traveled widely, a friend of Ferdinand Hodler, Rodo (Auguste de Niederhäusern) and other outstanding Italian artists. Through his long and affectionate association with Cuno Amiet, the manifesto of the Pont-Aven school reached as far away as Bregaglia, and with it the major features of the great French culture.

Around 1910 the Giacometti family already possessed reproductions of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Seurat, the Nabis and the Fauves. In the family home one can still see the clearly Gauguin-influenced woodcarvings that Giovanni himself sculpted for the room they used in the winter.

Here in this exceptional cultural climate and under his father’s guidance began the first apprenticeship of Alberto Giacometti, who thanks precisely to that initial formation, and despite having subsequently attended art schools and academies, may be considered essentially a self-taught artist, having acquired his art above all from his father for whom, artistically speaking, he always bore great respect.

It is therefore impossible to write about Giacometti without remembering his valley: its horizon stretching along the ridges of the mountains, its meadows, its stream, its forests and rocks, the long shadow of winter, the village and house where he was born, his family, his father’s studio, the apple orchard, as well as the faces and dialect of his fellow countrymen.

Equally, it is also impossible to forget what Paris meant to him: the Latin Quarter, his atelier, his humble abode, the sidewalk cafés, La Coupole, the Rotonde, the Dôme, Les Deux Magots, Lippi, the Sphinx, the Egyptian, Chaldean and Sumerian rooms of the Louvre, the Museum of natural history, the models, their faces, his friends, the people encountered even just once, his contacts, his relationship with the cultural climate of Paris and its leading personalities.

But it must also be said that aspects of his native land – which can be described as rough, stony, powerful, solemn, unadorned, solitary, and primitive – remained in him to the end, like clay deposited on the deepest roots of his personality, and these are also attributes ascribable to his sculpture.

Assailed by doubt, hesitation, and fear of “not succeeding,” Giacometti may be said to have lived an altogether dissatisfied life, albeit sustained by hope and guided by unfailing intuition and strong will-power. He had an enormous capacity for work, as if he were resolutely pursuing life itself through his efforts, or that part of life that most eluded him.

Work was his only discipline, obeyed in the same way a monk observes the strict rule he has chosen with absolute devotion. To be a totally free and independent man, he had reduced his material needs to the absolute minimum, living a hand-to-mouth existence, almost fortuitously. He was nevertheless open-handed, in spite of the fact that he neither possessed nor wanted to possess anything. He had no real home: like a child, he said, I always return to the only home I have, to my mother’s house. Throughout his life he was content to work in a small, dingy studio that any Fine Arts student would have refused. When his success, albeit belated, finally came he remained unaffected, going on with his usual life, maintaining the same needs and habits as before. Outside of work, his only need was for human contact, which he constantly sought and never refused, no matter what.

He always worked with endless energy, taking no rests or breaks, with the precise intention of physical self-abasement, of silencing within himself any conditioned idea or act, and in so doing minimizing any rational predominance of the intellect, so as to escape from its control and be totally free from any burden of reality or from any memory of it. It is a pity that the Italian most like him, Bruno Barilli, did not write about Giacometti the man.

To find the root from which all of Giacometti’s art springs, the solid foundation on which rests, means first of all to come across drawing: which is in effect his way of seeing things. If the development of his sculpture involved second thoughts, uncertainty and false starts, or if it was not until the 1940s or so that he was able to clarify his vision in that medium, the same cannot be said of his drawing (and painting), which from the outset improved steadily, advancing in a unswerving, resolute direction: that of reality. With the exception of a few drawings from his typically surrealistic period, from youth to maturity his drawing was simply the main means through which he could see more clearly, to better understand, copy or study reality. Such means freed him of all uncertainty. Only then did those means present in his drawing become “actors” in his sculpture. What he found in drawing he put into sculpture and what he found in sculpture he returned to drawing.

But it must also be said that with the exception of a few quick sketches or short annotations, he never made drawings as preliminary studies or projects for sculpture. His drawing is, therefore, artistically a genre on a par with his sculpture and painting. On the paper, the signs reflect the immediacy of intuition; they are the outline of his search, the proof of what he was able to master. Drawing was the acid test through which his search for reality was carried out day after day, leaving out the mere aesthetic aspects which for him, as such, had never existed. It was a way of rationally practicing and refining his artistic skills. In a few stupendous works he has given us perhaps the greatest testimony of his qualities, the most candid poetic confession of his ideals, and the main proof of his genius. He could draw anything and everything that caught his alert and curious eye: he did not need to arrange sittings or choose subjects, but could work with anything at all; a series of objects displayed haphazardly was enough to awaken his impulse and need to draw. With rapid and precise strokes, the paper came alive with a hundred different features, a hundred lines chasing each other, meeting and twisting together, all seeking the same thing. Talking about Giacometti’s drawing is like talking about his sculpture, given their interchangeable and complementary results. A luminous kind of drawing full of volume and color, analysis and synthesis, done with force, almost searching for what lies behind the objects in order to give them greater volume and the right expressive perspective: a clear, revealing kind of drawing in which second thoughts and false starts remain on the surface of the paper, becoming as expressive as the lines themselves, which seem to start from preordained point so well chosen as to appear fortuitous. They are placed in such a way on the drawing paper that the white background seems to have been instinctively left there as an integral proportional element showing a simple and expressive balance. His attention concentrates on a single detail that will then represent the fulcrum of the drawing and from there, from that specific detail analyzed, dissected to an improbable degree, everything originates, creating a harmonious form that one would say had been wholly perceived beforehand, so as to proceed rapidly, continuously, concisely, and naturally throughout the drawing.

The same procedure is applied to sculpture: the shaping of a form, the creation of a surface, of a perspective, of a projection, along with the carving of a feature or a shadow. To see Giacometti working with his fingers, which became tools for him, holding a penknife like a pencil, was like seeing him drawing. But now he was drawing in the air or in space, where he then came across a resistance that through a minimum indispensable volume became life, expression. The same gestures, the same starting points and the same second thoughts were repeated almost automatically; a movement coming and going rapidly, backwards and forwards, leaving a trace, a mark quickly erased and remade, by sudden modifications, discards and changes that went upwards, downwards or sideways. A laborious effort that must have been quite demanding for him. «Il n’ya plus que la réalité qui m’intéresse et je sais que je pourrais passer le restant de ma vie à copier une chaise», he wrote not long before he died. This thought of his contains everything that entire pages written by others would not be able to express.

This brief analysis cannot take into adequate consideration all the phases of Giacometti’s career, particularly the intermediate phases. In his biography and in the plate captions we have, though briefly, mentioned the various phases and chronological developments. Here instead we particularly want to concentrate on his most important achievements, the definitive ones, which in the last analysis were closest to his idea of art. The ones that he pursued so obstinately and perhaps reached when they were about to elude him, so that his insistence became inexorable, breathless, without respite. His work is so complex that to be equal to it and follow it closely, the resulting flow of thoughts, sentiments and impressions appears inexhaustible. One wonders – and this is merely an observation – why Giacometti himself, alone among his contemporaries, and his works were of such interest to poets and writers. Why else does his bibliography contain not only the names of art critics, but also those of André Breton, Tristan Tzara, Michel Leiris, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jacques Prévert, Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, René Char and Olivier Larronde?

His work was a message, therefore, that went beyond merely formal results, and poetically penetrated deeply into something that closely touched the condition of modern man. One day, by chance, I saw a large quantity of sculptures arriving in the enormous storerooms of a museum, that is to say a place where works of art only pass through during the preparation of a sculpture exhibition. Some of the statues were placed on the floor, some were lying in open crates, others were already on trolleys or temporary pedestals, and many others were gradually being unloaded from vans. There were all kinds and sizes of statues, created by the leading modern sculptors. Giacometti’s statues, which the porters handled more carefully not only perhaps because of their evident fragility, seemed to be the least “statue-like” of all, the least compliant with what is conventionally considered to be a statue. They were there on their own, isolated among the others, as if they really were something else, something that put me in a state of anxiety as if they were not statues but mysterious, magic idols or fetishes of an unknown religion mainly based on the cult of the dead. More than the others and in a way that those other works had not even touched on, they seemed to be the most “real”: presences, human beings. While standing before them, the words of Henri Maldiney seemed the most apt description: «Les formes de Giacometti disent l’acte originaire par lequel l’homme surgit comme présence, sa venue à soi dans l’ouvert nu.» They had a gaze that contained unspoken words. They were the only works that made me wonder where they came from, also because I felt they all came from the same place. The other sculptures, even those that apparently might interest me even more, did not seem to contain such a seductive stimulus to seek the germ of their provenance, nor did they carry it inside like a seed, like a provocative, anonymous and disquieting source. Giacometti sought to dominate solitude. And, in truth, that same solitude, which was similar to his own, seems at times to pervade some of his works. In these sculptures he left in shadow what did not deserve to be further pursued: he highlighted only what was dearest to his heart, what he considered essential and plausible. It is as if he wanted to illuminate only that unique unrepeatable instant in which man shows his true self, when he is not simply apparent, but most real. He placed this “man” of his in a space that is very close to emptiness and silence. He had the enormous courage to start all over again, as if, timewise, he were one of the first sculptors of his time to really look at the nature of man, and in that nature – as an artist of the 20th century – he had discovered a sort of still unexplored desert. In that man there was an image – the image which was made to advance at the right distance from the abysses of time and space, before our very eyes. How did it reach us, though, and in what manner? Is it the fruit of an action only half-completed, which has gone has far as it could? Or is it what is left of a semi-destroyed image? Is it the result of an action of destruction, the sign of an ending? Is it instead the sign of a beginning? Is it something that has remained, that has survived? Or is it in effect something that is starting to exist, that is coming into being now in order to live? Why is it that each time one sees a sculpture of his, one has the impression of seeing “something” for the first time? Why does one wait for a sound, like that of a voice, to break the silence surrounding it? Many insist upon saying that starting with a figure or head of normal dimensions, Giacometti continued to subtract until he made it thinner: on the contrary, I believe that all the volume in his sculpture is only that which he wanted to achieve or, more probably, that which he succeeded in achieving. Precisely because he started from zero, and because in all honesty he brought out in a sculpture only that which the creative power within it allowed him to, he never “finished,” he only “made” what he could, without rhetoric, without deception, without second aims or for aesthetic goals. His figures stand erect and face frontwards. We look at them and they look at us. They do not turn their backs on us, nor are they deceitful. In the world in which they are confined there is no place where they can retreat or hide away: they have freely chosen to remain immobile there, vulnerable prisoners, eternally standing erect. When his models were posing the dimensions of his studio, as narrow as a cell, seemed to open up, becoming an immense stage, an echoless chamber for specimens of an unadorned and anonymous humanity, which he always saw as if for the first and also the last time, before letting them leave for what seemed to be their most likely destiny: a journey without return. From them he drew the essence, the profound rather than only visible fount of their existence.

His sculptures seem to conclude that man’s only destiny is to die as a stranger among men. Giacometti’s sculptures are so indifferent and extraneous, without joy, so solitary, fated and lost, that they reflect a deep awareness of sorrow, seeming to possess nothing other than their extraneous stare whose confines only Giacometti, I imagine, could sense. Where should they therefore be placed? What is their ideal location where their vitality can be strengthened in all its magnitude and their expressiveness revealed to its highest degree? Should they be placed in elegant houses, in brightly lit glass cases, in the impeccable halls of museums, in flower gardens? Or perhaps in those places where solitude and desolation reign supreme, moors or deserts, making it clear that these sculptures are relics of the world today? In this way they will be authentically revealed for what they are: clots of life, the last surviving semblances of the human figure to which Giacometti restored its ancient dignity just when it seemed to be irremediably lost. They could thus be seen as an achievement, the only possible one for him, a message of faith and hope in man, despite their outward appearance. In reply to the question of whether it was still possible, today, to make of sculpture a plausible reality – a question that was his tormenting obsession throughout his life – Giacometti has certainly replied with extreme sincerity and clarity in such a way as to leave no room for doubt, even though his modesty and spirit of self-criticism led him to doubt this. «Pendant vingt ans j’ai eu l’impression que la semaine suivante je serais capable de faire ce que je voulais faire», he once said and, perhaps, in his heart he awaited this “week” until the last days because in life he was always fascinated by the act of seeking: this act of desperate and unending research and struggle certainly gratified him far more than any pride he might have derived per se from the hypothetical certainty of having achieved something, from having discovered a truth in which to believe.

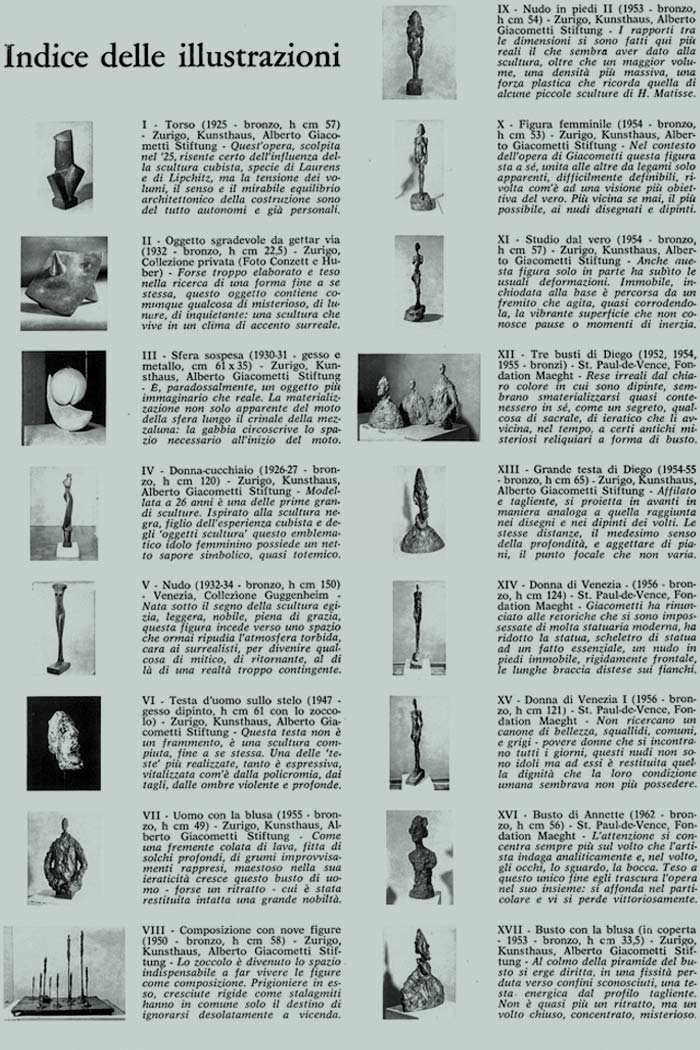

Index of the pictures

I – Torso (1925, bronze, h 57 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. This work made in 1925 shows a clear Cubist influence, especially from Laurens and Lipchitz, but the tension of the volumes, the remarkable sense of architectural balance of the construction, are completely autonomous and already personal.

II – Disagreeable Object to be Thrown Away (1932, bronze, h 22.5 cm) – Zurich, private collection (photo Conzett & Huber). Perhaps too elaborate and bent on achieving a form as an end in itself, this object in any case contains something mysterious, lunar, disturbing: a sculpture that exists in an atmosphere with a surreal tone.

III – Suspended Ball (1930-31, plaster and metal, 61 x 35 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. Paradoxically, this object is more imaginary than real. The materialization of the movement of a sphere along the crest of a crescent is not only apparent: the cage limits the spaces necessary for the start of the movement.

IV – Spoon Woman (1926-27, bronze, h 120 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. Shaped at the age of 26, this is one of the first large sculptures. Inspired by African sculpture, offspring of the Cubist experience and the “sculptural objects,” this emblematic female idol possesses a symbolic, almost totemic air.

V – Nude (1932-34, bronze, h 150 cm) – Venice, Guggenheim Collection. Influenced by Egyptian sculpture, light, noble, graceful, this figure strides towards a space that now repudiates the murky atmosphere cherished by the Surrealists, becoming something mythical, recurring, beyond contingent reality.

VI – Head of a Man on a Rod (1947, painted plaster, h 61 cm with base) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. This head is not a fragment, but a self-contained sculpture. It is one of the most fully developed of the “heads,” highly expressive, energized by the polychromy, the cuts, the deep, violent shadows.

VII – Man with Smock (1955, bronze, h 49 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. Like a trembling flow of lava, dense with deep crevices and suddenly congealed clumps, majestic, stately, this bust – perhaps a portrait – of a man conveys a sense of great nobility.

VIII – Composition with Nine Figures (1950, bronze, h 58 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. The base has become the indispensable space to array figures as a composition. Prisoners inside it, rigidly extending like stalagmites, they share only the fate of desolately ignoring each other.

IX – Standing Nude II (bronze, h 54 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. The relationships between the dimension have become more real here, which seems to have given the sculpture not only greater volume but also a more massive density, a plastic force that reminds us of certain small sculptures by Matisse.

X – Female Figure (1954, bronze, h 53 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. In the context of Giacometti’s oeuvre this figure stands apart, connected to the others by bonds that are only apparent and hard to define, given the more objective vision of reality the work implies. If anything, it is closer to the drawn and painted nudes.

XI – Life Study (1954, bronze, h 57 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. This figure too has undergone the usual deformations only in part. Immobile, fastened to the base, it is shaken by a trembling that brings alive and almost corrodes the vibrant surface, which knows no rest, no moments of inertia.

XII – Three Busts of Diego (1952, 1954, 1955, bronze) – St. Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght. Rendered unreal by the pale color of the paint finish, they seem to dematerialize, almost as if they contained something sacred and stately, like a secret that brings them closer, in time, to certain mysterious antique reliquaries in the form of a bust.

XIII – Large Head of Diego (1954-55, bronze, h 65 cm) – Zurich, Kunsthaus, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung. Tapered, sharp, projected forward in a way similar to the one achieved in the drawings and paintings of faces. The same distances, the same sense of depth, the same protrusion of planes, the unvarying focal point.

XIV – Woman of Venice (1956, bronze, h 124 cm) – St. Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght. Giacometti avoids the rhetoric that had taken hold of much modern statuary, reducing the statue – or more precisely its skeleton – to an essential presence, an immobile standing nude, rigidly frontal, with long arms extended at the sides.

XV – Woman of Venice I (1956, bronze, h 121 cm) – St. Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght. Pursuing no canon of beauty, squalid, common and gray – humble women one might meet every day – these nudes are not idols, but they are granted that dignity that their human condition no longer seemed to possess.

XVI – Bust of Annette (1962, bronze, h 56 cm) – St. Paul-de-Vence, Fondation Maeght. The focus sharpens on the face, which the artist analytically investigates, and in the face the eyes, the gaze, the mouth. Driven to a single aim, he neglects the work as a whole: he concentrates on the detail, and gets victoriously lost in it.