J’attends vos silences, espaces

pour devenir un astre pur.

Max Jacob

Born of a curb of Molera stone pilfered in the night there rose, as pure as myth, soaring upwards to the eternal feminine, that ineffable head from 1911-12 by Amedeo Modigliani, seen again today – on 3 March 1981 – at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. In 20 days’ time, the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville will present a major retrospective of his work. In the certainty and regret of not being able to still be here for the occasion, returning to my hotel I try to trace back, in memory, through the entire history of Modigliani as sculptor, starting precisely with her, with that head observed, loved and re-observed in the morning with the intensity of a farewell. Like someone who has received a gift that has made him happy, I fall asleep, promising myself to no longer interrupt these reflections of mine till they have reached their conclusion.

Modigliani was a sculptor of stone, not of clay, which he called “mud”: a stonecutter, not a shaper of things with the fingertips. Legend has it that some friends gave him some oak railroad ties to sculpt. But the only head that has reached us is hesitant, amorphous if not apocryphal: in any case, it would seem to indicate that wood was not his ideal material.

Still not possessing those particular characteristics that were to emerge later, the sole specimen cast in bronze, 23 centimeters in height, at the Museum of Seattle, is undoubtedly a very youthful piece, brought perhaps from Leghorn to Paris. Still not possessing those particular characteristics that were to emerge later, the sole specimen cast in bronze, 23 centimeters in height, at the Museum of Seattle, is undoubtedly a very youthful piece, brought perhaps from Leghorn to Paris. I suppose that from that time on he rarely modeled clay, and it is certain that he made no more sculptures in bronze. The bronzes, made from castings of some of his stones, have been put into circulation on the market only in recent years!

Of the 25 or 26 sculptures attributed to Modigliani, how many were made by him? It is hard to say, given the clear, undeniable differences in quality that exist between certain specimens and others. On instinct, I believe they are all authentic. And then, how many of his sculptures were destroyed, how many were lost or remained unfinished, or were finished by others?

All the sculptures are in sandstone; only one is in marble. The head belonging to an unknown collection that was shown in 1930 at the 17th Venice Biennale is the only signed piece. The period of sculpture, for Modigliani, began in the fall of 1909 and lasted four years.

This is certainly not a parenthesis, but the very fulcrum of his personality. He sculpted by directly cutting until 1913; after which, lacking the strength that is demanded by sculpture, he shifted back to only painting, which he had never abandoned.

Even when he paints, at least until 1916, Modigliani continues to sculpt. This might seem like a paradox, but I feel it is true.

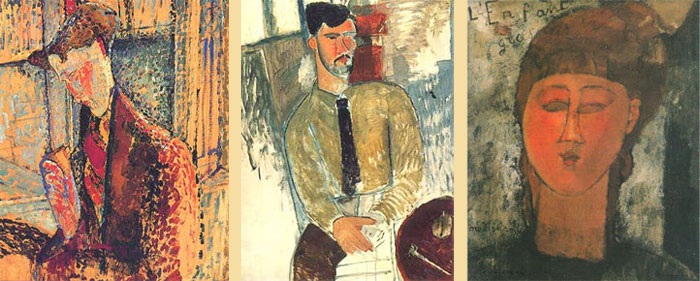

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Burty Haviland, 1914; Portrait of Henri Laurens sitting, 1915; L’enfant gras, 1915

The pursuit of form is practiced in a similar way as in the sculptures, the modeling does not get weaker, nor does the color, as happens in the last exhausted paintings of his short existence. It becomes pithy, dense, highly expressive: the painted forms seem to be shaped, and even the color takes on a new intensity and an extraordinary vigor as in certain antique polychrome sculptures. The portraits are almost monochromes, where red prevails over shades of ochre and violet.

The drawing in certain oils belongs to sculpture, or at least to the way of drawing of Modigliani the sculptor. For example, in the Portrait of Frank Burty Haviland (1914) the head, seen in profile and bent forward, is a “form” that rests on the bright red of the shirt and the brown-violet shoulders as if on a base. The skull is stretched back, and the continuous curve of the neck and its nape – a true force line – is a necessary, indispensable static support.

The Portrait of Henri Laurens seated (1915) also follows sculptural modules: the neck is a cylinder, the bust just barely touched by ochre, especially in the left part, is solid and blocked out in terms of volume like an archaic statue.

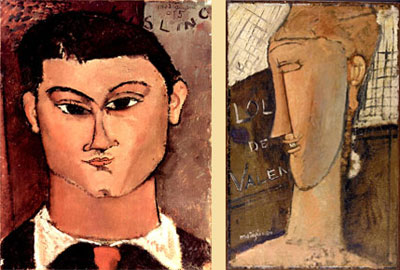

The warmth, the volume of the face, the neck, the eyes without pupils, the braids of that enchanting painting that is L’enfant gras (1915), which I have loved so much and returned again and again to see in the house of friends, always as if it were the first time, can also suggest the idea of a fascinating sculpture. The Portrait of Moïse Kisling (1915), a sort of asymmetrical face, is entirely caught up in a fast-paced pursuit of plastic elements. The drawn structure of the image of Beatrice Hastings (1916) – I am alluding only to the head and the neck – seems like the painted transcription of one of the heads sculpted in stone, just as the Lola de Valence (1915), seen in profile, is a true painting-sculpture.

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of Moïse Kisling, 1915; Lola de Valence, 1915

From 1916 on, in Modigliani, there is only the triumph of painting, as the figures are humanized, losing something of the stateliness typical of the sculptures.

He is now only a painter of portraits, of nudes with stupendous forms and bright colors, in which – unlike what happens in the sculptures – a noble, pure sensuality, never indulgent or vulgar, comes to the fore.

Alongside the true sculpture, in the entire oeuvre of Modigliani, there is a fertile production of drawings, in which the formal definition is progressive, as if striving to achieve a purification of the form; a gradual elimination, a tenacious refinement, advancing towards an unconditional, pure, total simplicity, without indulging in a mannered grace, an intentional expressivity.

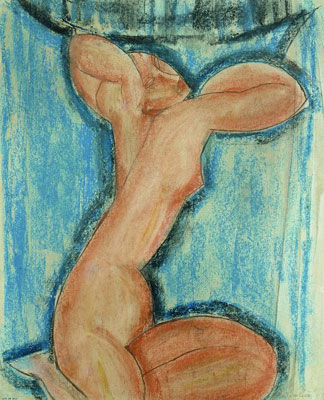

Like the gouaches and watercolors, the drawings of caryatids, nudes and heads are all sculptures that could be made and unfortunately were not.

I would also say that the drawings of heads, certain profiles, certain “elevations” are those of an architect-sculptor. Of a sculptor-stonecutter, i.e. he who seeks the form through the exercise of thought, looking inside himself and on paper before arriving at the stone.

It is plausible to think that at the start of the sketching, like any other sculptor, Modigliani may have used charcoal or a stone marker to trace on the surfaces of the selected block some cursory echo of his own designs, because in his sculpture the plastic development of the forms and volumes can be sensed as having been already nurtured in drawing.

I do not want to assert that he made a drawn maquette for every sculpture, which would have put a chill on the execution: I simply want to emphasize that the development of the form came “upstream,” facilitated by the exercise, the incessant discipline of drawing. A formal preparation that in the act of implementation in the block was positively and lyrically set free in direct forms that immediately came to life. He was not a virtuoso, and therefore I believe he rarely improvised on stone.

Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, 1911-12, Dusseldorf, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

Certain heads seen from the front or in profile, rather than freehand seem to have been made with drafting tools: the sign is so decisive, executed, definite as to make it seem as if he had designed capitals and columns, rather than heads. In other cases, the contours are so forcefully emphasized and thickened as to make the drawing seem like a true “section.” In a head of a Caryatid (1911) belonging to the collection of Paul Guillaume, research on curved lines emerges that might lead to a reckless mental association with Oskar Schlemmer. Several caryatid heads are transformed into corbels, Doric or more precisely Tuscan capitals, with abacus and echinus, straight fluting, astragal and necking. The influences become more Greek than Romanesque or Gothic. Only in a few isolated heads, of men or women, can we glimpse – but only to some extent – the appeal of certain African sculptures: for example, of Bantu sculptures, the long Ngil masks of the Fang people of Gabon, the graphics of Ashanti dolls from Ghana, the heads of Guro weaving shuttles, and above all the typical grace of the “Greeks” of Africa, the Baoulé. In a Dogon lock I have owned for years, each time I look at it, even fleetingly, I can glimpse a Modigliani, though I could not say why. Perhaps it is only the suggestion of that narrow, lengthened form, its way of finishing like the prow of a dugout canoe. A persistent shamanic charm still reaches me from that object.

The drawings, gouaches, pastels and watercolors of caryatids, often in large size, are more determined, freer, more confident and successful, perhaps, than the sole caryatid sculpted in stone in 1912-13, which in my view suffers from its small size, just 92 centimeters.

I presume that had he had the possibility, the good health and strength, many of those drawings and gouaches would have been transformed into caryatids or nudes sculpted in natural size or even larger, because this was one of the dreams of the sculptor, though unfortunately not in his fate.

The nudes of standing, kneeling or crouching women, from the years 1910, 1911, 1912, are exclusively drawings for sculptures, of true statues of women studied and specified in terms of every form and volume. But the highest tribute, as a real masterpiece, should go to the large colored caryatids, to those sketched out in blue crayon, which he called “colonnes de tendresse,” in which the loftiest plastic ideals of Modigliani seem to have been approached, if not reached.

His sculpture is simultaneously mother and daughter of his drawing. As a result, we cannot talk about the drawing without putting it into relation with the sculpture; nor can we speak of the sculpture without tracing back to the drawing. Only in this way is it possible to observe his way of making sculpture with the fullest awareness.

I remember a photograph from 1912 that shows Modigliani at the Cité Falguière where he had a studio on the first floor and where, in the courtyard, he rough-hewed his stones. Modì is standing beside a large head in progress, firmly placed on a massive wooden trestle. The photograph is rather out of focus and what stands out most, also due to its pallor, is the large spherical volume of that face with its Attican air that emerges, shifting forward with density and force, from the back part, barely roughed out as a pillar. An amazing image, the space of an instant, a pose, the act of crossing the arms and looking at the camera, and everything is already finished even as it happens

What remains, blindingly, is the fullness of that “egg” of absolute values, and the imaginary echo of the confident friction of the tools that forcefully drive into the matter to seek the form.

Though it was ordinary stone, for me it has all the crystalline glow of Parian marble. Who initiated Modigliani in the field of sculpture?

Let’s not forget that in 1909 one of the neighbors at his studio in Montparnasse, also at 24 Cité Falguière, was Constantin Brancusi, who had reached Paris in 1904, and was introduced to Modigliani by Dr. Alexandre. Driven by authentic instinct, in sculpture Modigliani acted as an autodidact, at most following a few precious, authoritative bits of advice. But I do not think there are definable influences.

The relationships with the sculpture of Brancusi – to which many try to trace back the work of Modigliani – are not particularly plausible. We might look at the Portrait of the Baroness R.F. in 1909, due to some slight similarity, which is an anomaly in the output of Brancusi. Manneristically stylized, with decorative overtones, it seems to have little in common – in plastic and poetic terms – with Modigliani’s “heads.” Certainly Brancusi taught him and guided him in the craft, as a great artisan, but stylistically he was never an influence, because their respective plastic and expressive concerns never converged.

Modigliani too wanted to create doors, architraves, intentional dialogues and juxtapositions of multiple sculptures arranged together; his greatest unfulfilled dream remains the “Temple of Humanity” for which he wanted to sculpt an entire series of caryatids.

These unfulfilled fantasies, these frustrated dreams, are what he has in common with Brancusi. Who only later, in 1937, was able to give concrete form to this way of making sculpture, capable of going beyond the single piece as an end in itself, to achieve something more: the silent monument of a certain vision and a certain philosophy of life, and also sculpture, but created for an audience much larger than that of a few individual admirers.

At Tîrgu Jiu, in Romania, Brancusi made an entire sculptural-architectural complex in which a precisely planned path unites the Gate of the Kiss with the Infinity Column and the Table of Silence. But works like Maiastra (1915), Mademoiselle Pogany in the first version (1913), Sleeping Muse(1910), reprised several times later, and the Prodigal Son (1914), to speak only of creations of the same era, are very far from the conceptions of Modigliani.

Brancusi, whose everyday reading matter was the Life of Milarepa, the Tibetan poet, yogi and hermit of the 11th century, was influenced by oriental philosophies and religions.

A poet in his own right, an assiduous and refined reader of the poets of the dolce stil nuovo, of Dante, Petrarch, Poliziano, Ariosto, Leopardi, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Lautréamont, D’Annunzio, Oscar Wilde and Apollinaire, Modigliani “surrounded by a compact ring of solitude” stubbornly turned around his “archetype,” alone, getting closer each time, intercepting here and there what was in the air, but remaining an extreme individualist in substance, a déraciné who had a style in sculpture that was his alone.

Like Brancusi, after all, he remained happily inert in the face of Futurism and indifferent to – or just barely grazed by – Cubism, that glorious Cubism on which the better part of the Parisian sculptors of the day were feeding, from Archipenko to Laurens, Lipchitz to Zadkine, who all became his friends as well. Referring to Laurens, Franco Russoli correctly comments: «The friendship between the two brought about reciprocal influences that took the form of a solidity of volumes, of structural synthesis, in Modigliani.»(2)

At this point I believe it is not possible to pretend to ignore that Modigliani saw and admired the drawings of Rodin, the true inventor of modern drawing with pure, rapid, continuous lines.

Did he get a chance to know the work of Wilhelm Lehmbruck, of his same age, certainly with more affinities to his work than Elias Nadelman, in whom (strangely enough, to be honest) he was interested?

He knew and admired Manuel Manolo, who at the outset had forms and subjects – nudes and caryatids – similar to his. Perhaps the early work influenced by Brancusi and the Cubists of the very young Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, six years his junior, who lived in exile in London and died in the war in 1915 at the tender age of 24, did not fail to catch his eye.

But Modigliani also met and spent time with other sculptors less in “glory,” like Léon Indenbaum of whom he made a portrait in 1915, or the Florentine Rosso Rossi, or the better-known Jacob Epstein who wrote about him, not to mention the brilliant Portuguese painter Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, a great admirer of Modigliani’s sculpture, who hosted a true exhibition of sculptures and gouaches in his studio on Rue du Colonel Combes in 1911. They were good friends, linked by mutual esteem as well as certain stylistic affinities. Unfortunately Souza-Cardoso died in 1918, when he was just 30 years old.

In his memoirs – Le maillet et le ciseau – Ossip Zadkine speaks at length of Modigliani; he was the person who introduced the artist to Beatrice Hastings.

One of the most reliable and engaged witnesses to the life experiences of Modì was Jacques Lipchitz, attracted by the “melodious impetus” and beauty of Modigliani. They met in 1913 at the Luxembourg Gardens one evening at sunset, when Modì, reciting verses from the Divina Commedia, was strolling together with “his” Max Jacob. After that they saw a lot of each other, with reciprocal visits to respective ateliers, involving frequent discussions on the art of “removing or putting.” One day at “La Ruche” Lipchitz introduced Modigliani to Chaïm Soutine, and later, in 1916, he asked him to do a portrait of himself and his wife, Berte Kitroper, following their recent marriage. The price asked by Modì was “ten francs per session, plus liquor.”

Moïse Kisling and Conrad Moricand, at the Hôpital de la Charité on 24 or 25 January 1920, made a clumsy job of the death mask of Modigliani; it was Lipchitz who filled in the missing parts and saw to the reproduction of 12 plaster copies to distribute to the artist’s relatives and closest friends.

I regret never having had a chance to read the Ricordo di Modigliani by Osvaldo Licini, published in the magazine L’Orto in Bologna in 1934; nor have I ever managed to get my hands on the Omaggio a Modigliani with its precious recollections published by Giovanni Scheiwiller way back in 1930; and I know little of the Tournant dangereux by the painter Maurice de Vlaminck, published in Paris in 1929.

Those who say that Modigliani’s sculptures are a perfect blend of cultures, from his contemporaries to the ancient Egyptians and Greeks, the Sienese painters and Tino di Camaino, African and Oriental art, especially that of the Khmer, are certainly far from wrong. But rather than influences, I would speak of assimilations that leave the forceful personality of Modigliani, as an independent protagonist, quite intact.

In the end, especially where painting is concerned, only Paul Cézanne – discovered at the first Parisian retrospective in 1907 – remained his sole myth, his true elective mentor. Throughout his life this example helped him to formulate his formal language in its primary structures; it was here that he learned the fundamental concept of synthesis and structure.

I would like to again call on Franco Russoli, who in 1967 wrote with great clarity: “Modigliani yearns for an artistic expression that is both ancient and new at the same time, as rich in cultural and existential motifs as it is simple and terse in its pure linguistic module: an art that is not nimble, but absolute.” (3)

Aristocratic and proud, untamed and brash, impertinent and generous, lyrical and full of pathos, in Amedeo Modigliani it is impossible to separate the personality of the artist from that of the man. Few have so thoroughly lived in the same way that they drew, painted or sculpted. A bitter angel, devoured by sublime fevers, he behaved like one who has a gift and knows he cannot keep it only to himself, but has to share it with others. He lived just as he created: poetically. His short, intense, tragic life is his foremost great, detached poem: the drawings, sculptures and paintings are merely its commentary, its trail. He has given us a beauty that also contained painful duties. He knew he had little time, and in that short space everything in him and of him was carried out in a sublime tension. An “admirable painter of pain,” as he was defined by Gustave Coquiot in his book Les indépendants in 1926.

Who better than Amedeo Modigliani could perceive, more than others and before them, the cry and the talent of that desperate brother-in-art that was Chaïm Soutine, introducing him to the impoverished and meager équipe of Zborowski? Shortly before his death, Modigliani told the latter: “Don’t worry, Léopold, since I am leaving you a man of genius in Soutine.”

His aestheticizing poetic, shot through with intimate lyricism, sustained by rigorous idealism and an always intact ethical tension, sought closed, uncorrupted forms, kept taut in a monodic expression, not extraneous to a tendency towards symbol.

His heads, especially those most pregnant with meaning, suggest the tenderness of a long, heartrending, smooth caress that becomes a pure act of love for the visage of woman.

Calcareous idols, mythical stone-women, archangels of a grace and a light that are utterly spiritual, these head-sculptures return anyone who observes them, captured by their arcane beauty, to those sacred springs that are the source of all the fertile periods of sculpture.

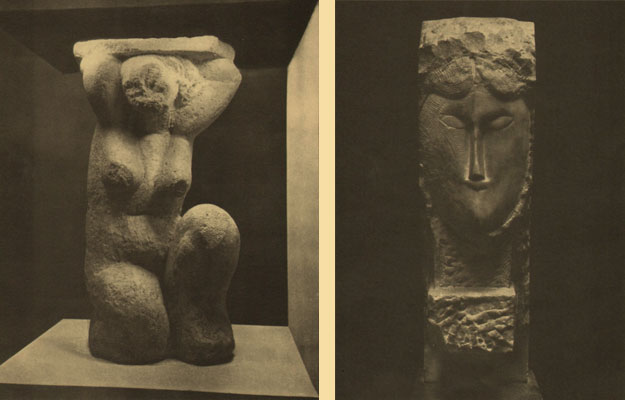

Amedeo Modigliani, Head, 1911-12, Tate Gallery, Londra; Standing Nude, 1911-12, Australian National Gallery, Canberra

Thus, for example, the Head (1911-1912) at the Tate Gallery in London: shaped like a blade, cut like a wedge, very narrow and entirely adapted to a vertical dimension deftly sustained by the straightness of the nose; the composition continues to the chin and terminates on a small and slightly convex base, undoubtedly desired by Modigliani himself. Certainly it must have had a much more specific title that the generic one of “head”; it appears that the artist called it “head for the upper part of a door.” The keystone, then, of the portal of that “temple of beauty” he had always hoped to build, in vain.

The set of the head-sculptures of Modigliani is divided into three different types.

The first contains three pieces, the most powerful, those with the fullest volumes, almost spherical, with round necks, strong as columns.

The second – only two in number – is the type where the use of a more porous stone causes a less rigorous, definite plastic volume; the facial features, not yet typified, are still almost naturalistic; maybe they were attempts at portraits, one with the bust, the other with a thick head of hair.

The third type, the most numerous and coherent, covers the typically “vertical” pieces, and here we undoubtedly have several masterpieces.

It should be pointed out that the size of these heads is constant, with an average of about 60 centimeters. This demonstrates Modigliani’s tendency to make things large, to prefer equal sizes or, more precisely, those larger than life, a frequent attitude in those who use stone as their raw material and shape it, as he did, by direct cutting, without models to be developed by enlargement.

Finally, in the sculptural output of Modigliani two other works remain to be considered, the only two nudes.

The first, in the G. Schindler collection of Port Washington (New York), with a height of 1.6 meters, is the largest sculpture by Modigliani. A copy of this standing nude (perhaps in cement) belongs to the Australian National Gallery in Canberra.

The compositional scheme and the research on certain details can be found in many drawings, such as the one in the Alsdorf collection of Winnetka, Illinois, or in the Nu debout de face (1910-1911), belonging to a private collection in Milan, or also the Nu debout de côté (also from 1910-1911), from a collection in Paris, and certain others.

It is the most “Asian” of Modigliani’s sculptures, due to its idol-like stateliness. The crossed arms, the small breasts placed very high, the full, spherical belly, like a cap, the wide hips, the strong, chunky legs roughly indicated, support what in my humble opinion is one of the most beautiful faces by Modigliani. A massive head, seen in relation to the proportions of the body, but very solid in its shaping, intense in its expression, with those eyes lost in meditation, thick and deep, enhanced by almost architectural moldings at the sides, making this a unique case amidst the more familiar heads.

Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, 1912-13, Museum of Modern Art, New York; Head, 1911-12, collection Jean Masurel, Roubaix

The second nude is the Caryatid of the Museum of Modern Art of New York. Due to its small size, as mentioned above, perhaps it is not equal in quality to the large drawings and gouaches that address the same subject. It lacks their rhythm, harmony, their complete and wide-ranging compositional thrust.

It is the last sculptural work in chronological order (1913). It seems like a draft, interrupted, in which the stone hints at becoming “flesh” as in the paintings of nudes.

It is already naturalistic, without the architectonic stylized features of the other sculptures. In plastic terms, it has stupendous segments, but perhaps it lacks the force to support that weight it would seem to be made to support. The fragment at the top is too slender, it should have been thicker, but the sculptor ran out of stone. I would like to add something regarding the Head belonging to the Jean Masurel collection of Roubaix. Made in 1911-12, it is the only one sculpted in marble.

The material, and not just the material used, makes it different from all the others.

The block from which it is made is a rather narrow, tall parallelepiped. To reduce it to the desired proportions Modigliani has drawn a corbel from the marble, from which the face, with the recess of the neck, protrudes like a mask. The sides are not sculpted but simply scraped with small parallel strokes; the workmanship varies: there is splitting, the point, the flat chisel, the toothed chisel, polishing. The material responds; it is as if Modigliani were drawing it, leaving all those signs, erasing none. He exploits the unfinished, sinking the nose and eyes, with tender touches at the hair. Everything in this face is concentric, as if that center from which everything moves was intended as the fulcrum of a mysterious message.

Modigliani has made it into one of his drawings in stone, one of the most beautiful, and from that small piece of marble a fragment of the universe has been released.

* * *

Alongside the credible and truthful texts by poets and artists that bear direct witness to his life, a great river of words has swept and flooded over the figure of Modigliani.

Pseudo-literary biographies in the form of novels, true and invented anecdotes, second-hand recollections and memoirs written simply because one day someone encountered him by chance or saw him restlessly roaming the cafes and bistros of Montparnasse.

Like all the maudits, he attracted and impressed many – unfortunately also the movies – a sorry fate shared with Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Gaudier-Brzeska, though a talented actor like Gérard Philipe has done everything possible to enter the character.

Fascinated by the unforgettable photographs of Modigliani when he was alive, almost as if to shoot some more, I would now like to transcribe some quick signature impressions, verbal flashes that are as eloquent as those images. Leaving to legend what belongs to legend, let us listen to the voices of those poets or artists who remembered him, in pursuit of some instants of his everyday life.

Let’s summon them and read them, if only in fragments, one by one, as witnesses.

Max Jacob

«His face was open, handsome, of a dark complexion. He had the bearing of a gentleman, but dressed in rags, and Picasso said that only he was able to dress entirely in velvet, with a workman’s checked shirt.»

— From a letter by Max Jacob to René Rimbert on 24 August 1923.

Ludwig Meidner

«Characters such as his cannot be modified, influenced, nor can they be induced to lead a more orderly life. […] He never had anything, because he was incapable of conserving. […] He had worries and difficulties on a daily basis, but this did not cast a shadow on his outgoing cheerful disposition. He loved life too much, which thus still flourished in a romantic aura.»

— From: Ludwig Meidner, The Young Modigliani: Some Memories (1943), published in Burlington Magazine, 82, April 1943.

Jacob Epstein

«At night he would place candles on the top of each [sculpture]. The effect was that of a primitive temple.»

— From: Jacob Epstein, Let There Be Sculpture, London 1940.

Jacques Lipchitz

«When I arrived at his studio, in the spring or summer, I found him working outside. Some stone heads – five perhaps – lay on the concrete pavement of the courtyard in front of his studio, and he tried to adapt them to each other. I can see him as if it were today, bent over his heads, absorbed as he explained to me how he had conceived of them as parts of a whole.

It seems to me that these heads were shown shortly thereafter, at the Salon d’Automne, in a stepped arrangement as if they were the pipes of an organ, to better express the musical sense he desired.»

After having recalled the agony of Modigliani on his deathbed, muttering verses in his delirium, Lipchitz movingly tells us of the death of Jeanne Hébuterne: «And then came the tragic news of the suicide of Jeanne. She was almost nine months pregnant with another child of Modigliani, and when she reached the morgue at the hospital she threw herself on Modigliani, covering his face with kisses. She struggled with the orderlies who wanted to drag her away, knowing how dangerous it was for a pregnant woman to touch the open sores that covered his face. She was a strange young woman, slender, with a long oval face that seemed almost white rather than rosy, her hair gathered in long braids; I was always struck by her almost gothic appearance. Jeanne went to her father’s place – she had been disowned because she lived with Modigliani – and threw herself off the roof of the house.»

Lipchitz concludes his recollections by writing: «[Modigliani] was aware of his gifts, but the way he lived was in no way an accident. It was his choice. […] He said to me time and again that he wanted a short but intense life – “une vie brève mais intense.”»

— From: Jacques Lipchitz, Amedeo Modigliani, Harry N. Abrams, New York 1954.

Lunia Czechowska

«Enfin j’allumai une bougie et lui proposais de rester diner avec nous. Il prenait plaisir à prendre ses repas chez nous et mon invitation arriva à le calmer. Pendant que je préparais le diner, il me demanda de relever la tête quelques instants, et, à la lueur de la bougie, il esquissa un admirable dessin, sur lequel il écrivit: “Life is a gift: from the few to the many: of Those who Know and Have to Those who do not Know and do not Have.”».

— From: Les souvenirs de Lunia Czechowska, written in 1953 and published by Ambrogio Ceroni in Amedeo Modigliani peintre, Edizioni del Milione, Milano 1958.

Enzo Maiolino

«And then appears a sort of workman dressed in worn velvet, with a large hat, his waist girded by a surprising woolen scarf. He crosses the street, comes towards us, introduces himself. It is the first time we hear “Modigliani.” […] The sun shone brightly on the day of his burial. On the morrow, at the funeral of poor Jeanne, the weather was dreadful and rainy. I put flowers on the tomb, later, with a bunch of violets whose scent I can still smell.»

— From: Enzo Maiolino, Modigliani vivo, Fògola Editore, Torino 1981.

Anna Achmatova

«Modigliani loved to wander in Paris at night, and often, hearing his steps in the slumbering silence of the street, I went to the window, and through the shutters I watched his shadow, as he lingered below my windows. […] Once we misunderstood each other about a date, and when I went to his place I found he was not at home. I decided to wait for a while. I was holding a bouquet of red roses. The window of the closed door was open. Not knowing what to do with myself, I started tossing roses into the atelier. Then, without waiting for Modigliani, I went on my way. When we next met, he seemed utterly amazed: how had I managed to get into the closed room, when he had the only key? I explained what I had done. “But that is not possible,” he said. “The roses were scattered so perfectly.”»